The two women were so involved in their conversation that they paid no attention to Chorch’s endeavours at the base of his cage. He had worked it open and was now climbing up, pressed hard to the outside, gripping the horizontal bars in his beak while his claws slipped on the smooth chrome of the vertical wires. But one thing was getting it open and another was this business of flying away. He had never flown, just exercised his wings as nature dictated in a clumsy imitation of the birds he had seen in the sky overhead and in the tree his cage was hanging in.

When the man with the moustache emerged from the house, Chorch clung to the wires on the outside of his cage without moving. But the man saw him, cried out and disappeared back into the dark doorway. The women glanced towards where the man had been and smiled condescendingly when he came out again with a cloth held in both hands. The cloth made Chorch recall the taste of blood. The man approached the cage. Chorch no longer hesitated. More than flight, it was a jump and a frantic flutter to the nearest branch of the tree, but the man came on holding the cloth in front of him. This time he had to do it. Bursting through the twigs and leaves, Chorch flapped his wings furiously and found himself launched in the air. Without being aware how, he managed to rise above the stone wall that loomed up before him only to crash painfully into a bush on the other side. Somehow he was not injured and his gaudy feathers were in place. He worked his way to the outside of the bush just as Moustache was climbing over the wall and the women were approaching on his left, waving their arms and calling out.

Chorch took off again, flying straight towards and above the advancing menace. His flight was rapid and not entirely out of control. Shortly after passing the people he veered to the left towards the relative safety of a stand of vegetation and, overflying the first clumps, came to an abrupt stop in the highest branches of a large almond tree. He remained still, recovering from the effort and the shock. In the late summer foliage his bright rusty, yellow and green plumage kept him well camouflaged from Moustache who several times trampled past under the tree making ridiculous noises. Most importantly, his colouring kept him hidden from the large black crows and the tawny kestrels overhead.

As the sun went down, Chorch dared another short flight to the greater safety of a leafy fig tree that also, he discovered, afforded him food and protection from the cold evening breeze. During the night, he was startled by the sound of a cat in the dry grass below the tree. He had to climb up higher into the milky branches that burnt his tongue, as the cat, attracted by his scent, reached the thicker bough where he had been roosting.

Despite the continual fear of people, cats and large birds, Chorch felt exhilarated by his newly earned freedom and spent the next day feeding on figs and flying from tree to tree. Hatched and bred in captivity, he had nevertheless inherited enough instinct to master the technique of landing on branches and tree trunks as well as navigating through fairly dense undergrowth. By the afternoon he had adapted well enough to risk a call but the appearance of Moustache a few minutes later taught him the wisdom of discretion. The trees were in a hollow surrounded by hills and the sun sank into the skyline early. Perhaps it was the prospect of another terrifying night that spurred him to do it but, as the shadows of evening climbed to the branch where he was nibbling the bark, Chorch took off and flew towards the rim of the bowl.

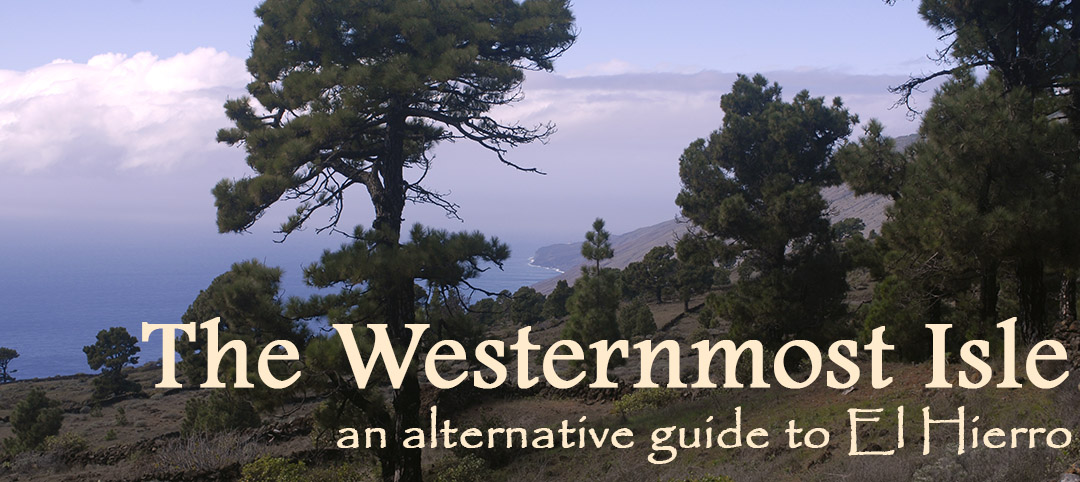

Once over the top, Chorch landed on the white skeleton of a dead fig tree. The sun in all its glory lit up in gold and warmth the abrupt coastline far below and the vast expanse of the ocean stretching to the west. His rest was interrupted a few minutes later by the sound of movement somewhere below him. At once he was in the air again, high over the rocky breakers and then the apparently calm sea, flying true towards the red setting sun. To him it was towards light and warmth. Or was it, perhaps, the response to some far deeper urge? He could not have known that America, the origin of his kind, lay on the other side of the ocean. And he certainly did not know that he would never reach it. But he was free.